THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE. ANA MARIA MICU

curators: Alina Șerban and Ștefania Ferchedău

Opening | Thursday, 2 March 2023, 18:00 - 21:00

Visiting schedule | 3 March - 1 April 2023

Wednesday - Friday, 16:00 - 19:00 (& by request)

Venue|The Institute of the Present, Erou Ion Călin 19 St., Bucharest

www.institutulprezentului.ro

___

5+5 / interview with Ana Maria Micu by Otto Felt

OTTO FELT: There is a question I ask at the beginning of every 5+5 interview about the artist’s specific understanding of their own context. What is your relationship with the local art scene, with the local social space in which you live? How do you analyse them? What are your expectations? What are you missing in your work?

ANA MARIA MICU: I have moved frequently as an adult, to different cities, and have not been shaped in relation to anything local, but rather as a person and artist who cannot find a place, and who periodically ends up abandoning almost everything she manages to build, except for a few carriageable things. So far I’ve been on an individual journey, and the way I relate to my colleagues is by receiving feedback from them every time I exhibit (which is important to me) and trying to incorporate it into my development. I have expectations and needs, but I’ve learned that I have no choice but to repress most of them. Very often I have felt that my artistic self stems from this inner space of violence and involves coping mechanisms, solutions that attempt to speculate all possibilities and resources, an equidistance to wonder and resignation. In this way I am functional, and in my work I lack nothing.

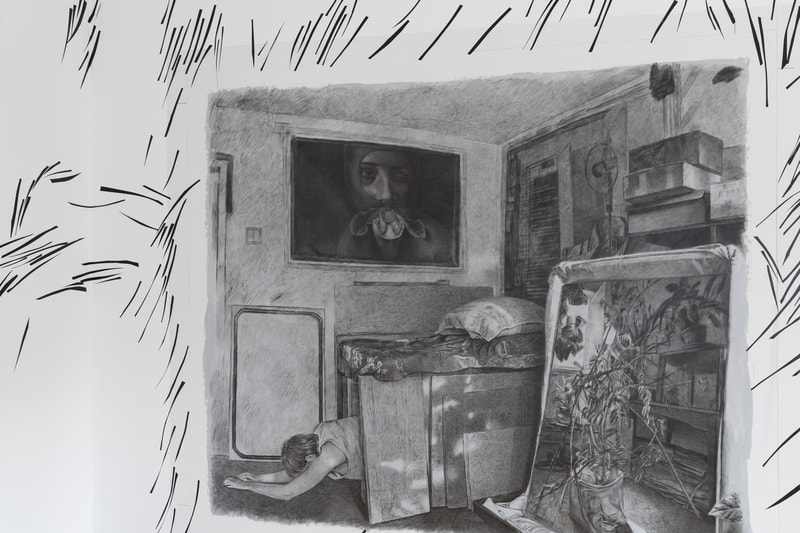

O.F.: Your persona, its environment, the privacy of the studio become the central subjects of your research. As a viewer I am drawn to the intensity of these personal moments, I become curious, I want to know more about who the author of these works is and I want to know what drives her to continue. How do you balance the relationship between “you” as the subject of the work and “you” as the creator?

A.M.M.: I am the subject of much of my work, and I don’t shy away from it. But this character does not exist, and I seek to bring it into existence by infusing it with a selection of character traits, emotions, and life experiences inspired by my own observations of myself. There are indeed intense scenes, because that’s how I want them to be. I want maximum contrast between the most mundane detail and the most profound human manifestation. I succeed to varying degrees, it’s an intuitive process that I don’t intellectually fully master, but I never lose my focus. I am an observer and I record by replicating what I observe.

O.F.: What is your relationship with painting, with pictorial realism? How important is drawing for you as a starting point for exploring themes?

A.M.M.: Following on from the previous question, realistic drawing and painting produces replicas, and the most beautiful thing about it is that no matter how well you replicate something, there are always differences that create a comparison between the subject and its representation. And this draws attention to how much time you spend in these states and practices. This creates a system consisting of the subject, the drawer, the act of drawing and the drawn image, and the totality of the phenomena that occurs in this system is its artistic part.

O.F.: Drawing is just one step away from animation. And it seems to be an important one for you, although your work is often read in the light of painting. How did this transition happen? And what was important for you to notice, and to portray, other than the canvas or paper?

A.M.M.: It’s not an obvious transition, and it took me many years to do it. The first observation that led me to animation is that when you draw, from the very beginning, when you mark the paper with the first dot, the image begins its process of emergence with a certain degree of independence that you cannot control. That first dot already has a role in the final image, but even though you have drawn the dot yourself, you cannot yet determine what that role is. The image is always ahead of you, and that has fascinated me for years. I wanted to document exactly what I was drawing, in real time, so I could then look back and see what was happening. If you have the patience to look, the animation unfolds in front of you which, to me, is absolutely charming, but it can also be boring if you are not interested. And to overcome this boredom, I have found a few formulas, and after several experiments, and I have worked some of them out. While documenting the appearance of a particular image, I now want to introduce moments of delight and reward for the viewer, who is given the opportunity to recognise moving characters, abstract signs suggesting figuration, or glimpses of narrative.

There are animations hidden within any painting or drawing, or any work of art. And I am referring to a processual, not to the concrete meaning of the term ‘animation.’ I use this medium in a different way to other artists. Linguistically, the correct form would be ‘moving images.’ The way I see them is without sound, always accompanying a static image, and displayed as close to the image as possible.

My animations are evidence that something happened.

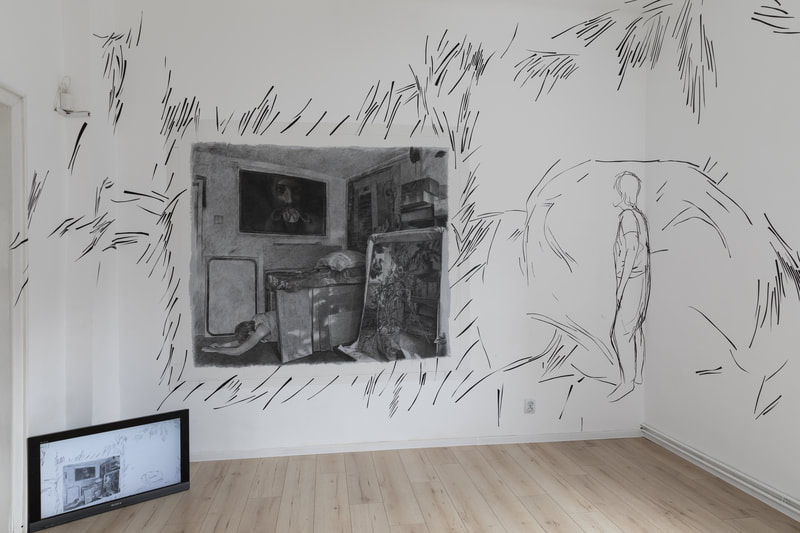

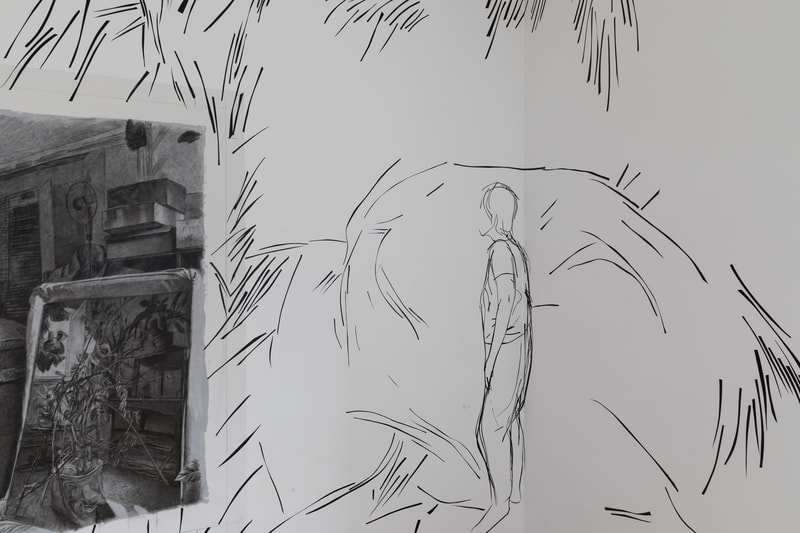

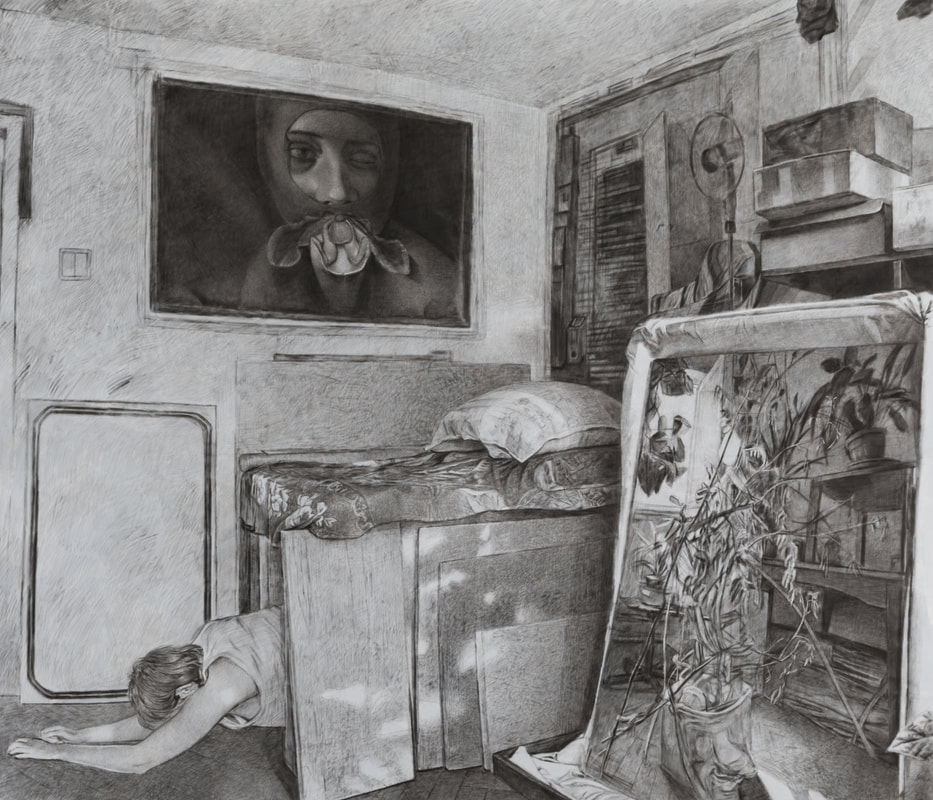

O.F.: Tell me about your intervention at the Institute of the Present and the main piece that will occupy the space: engaging activities, …Back to All NightCrawler. We find you in the studio, in the midst of (somewhat ambiguous) activities; we are invited to look around your studio space filled with other works, recalling the pictorial technique of mise en abyme so loved by certain Flemish or Spanish painters. There are many interpretations, of course, and we can imagine our own scenario, our own ways of working with these aspects of personal life. They can reshape generic answers about the condition of the contemporary artist, but at the same time they help us understand who Ana Maria Micu is and what her world is like.

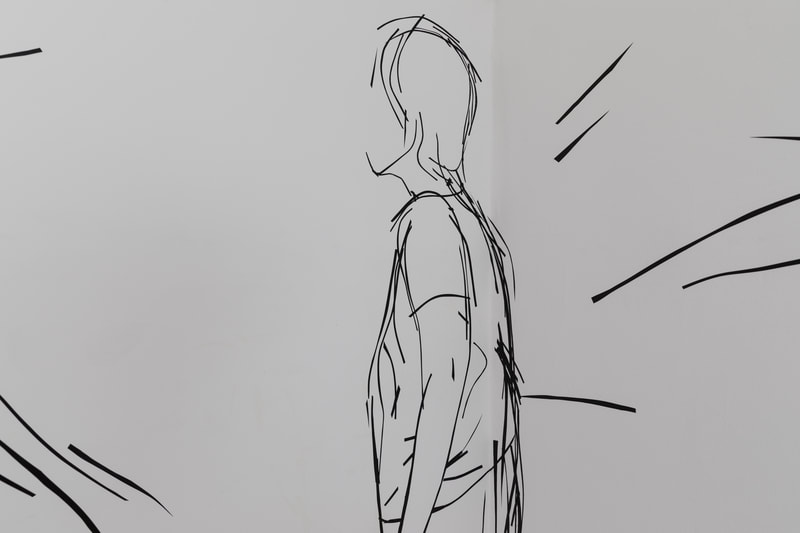

A.M.M.: The idea behind this work came to me when I suddenly noticed that I could fit in this place where I usually keep a box, constrained. The space left after removing the box, where it fits perfectly, is too big for the shape of my body, and it may even look like a miniature home, an improvised shelter in the corner of a room. Or it may look like an entrance to some underground place of immense proportions, where I could fall or be thrown into. There is some intentional ambiguity, allowing for multiple interpretations. It is good to keep the work open. And I am opening it up even more with this drawing spreading into a mural made of black adhesive cut-outs, with a more graphic look, which is the premise for an animation in which a character inspired by a video of me stands up from a crouched position.

___

ANA MARIA MICU is a Romanian visual artist from Botoșani. She mostly paints, but sometimes switches to other mediums, such as drawing and animation. She uses as a source ideas and images that she observes in relation to changes in her living space, in which she also works, or negotiations on resources required by an ambition to garden in inappropriate conditions.

OTTO FELT is a German-born writer based in Rockport, Massachusetts. Felt studied and teaches comparative literature and art history, and aspires to devote himself entirely to writing and publishing his novels. He is a collector of artist books, with a particular interest in Eastern European and South American art.

___

In the frame of the THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE initiative, the Institute of the Present puts forward a series of interventions taking place in its own working studio in Bucharest, addressing the present and triggered by the way in which the independent artistic platforms and artists choose to respond to the energies of the context in which they operate. THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE is above all conceived as a place for dialogue, sharing of individual and collective experiences that are hosted in the septic terrain of the white cube, but in a working studio of 50 sqm. THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE is conceived by Alina Șerban and Ștefania Ferchedău in the frame of the artist and theory resource platform the Institute of the Present.

The series is organised in 2023 in the frame of the residency project “COLLEGIUM. A Possible History of the Invisible”. Cultural project co-funded by the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. Visual identity: Daniel & Andrew Studio (Andrei Turenici)

The project does not necessarily represent the standpoint of the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. AFCN cannot be held liable for the content of the project or the manner in which the outcomes of the project may be used. These shall devolve entirely on the beneficiary of the financing.

Contact: [email protected]

MEDIA REFERENCES

[text, EN] Maria Mănăilă, Ana Maria Micu – Left Hand to Distant View, Contemporary Art Friday, 14 April 2023

[audio, RO] Parkour sonor / Ana Maria Micu, The Institute of the Present Podcast, 27 martie 2023

curators: Alina Șerban and Ștefania Ferchedău

Opening | Thursday, 2 March 2023, 18:00 - 21:00

Visiting schedule | 3 March - 1 April 2023

Wednesday - Friday, 16:00 - 19:00 (& by request)

Venue|The Institute of the Present, Erou Ion Călin 19 St., Bucharest

www.institutulprezentului.ro

___

5+5 / interview with Ana Maria Micu by Otto Felt

OTTO FELT: There is a question I ask at the beginning of every 5+5 interview about the artist’s specific understanding of their own context. What is your relationship with the local art scene, with the local social space in which you live? How do you analyse them? What are your expectations? What are you missing in your work?

ANA MARIA MICU: I have moved frequently as an adult, to different cities, and have not been shaped in relation to anything local, but rather as a person and artist who cannot find a place, and who periodically ends up abandoning almost everything she manages to build, except for a few carriageable things. So far I’ve been on an individual journey, and the way I relate to my colleagues is by receiving feedback from them every time I exhibit (which is important to me) and trying to incorporate it into my development. I have expectations and needs, but I’ve learned that I have no choice but to repress most of them. Very often I have felt that my artistic self stems from this inner space of violence and involves coping mechanisms, solutions that attempt to speculate all possibilities and resources, an equidistance to wonder and resignation. In this way I am functional, and in my work I lack nothing.

O.F.: Your persona, its environment, the privacy of the studio become the central subjects of your research. As a viewer I am drawn to the intensity of these personal moments, I become curious, I want to know more about who the author of these works is and I want to know what drives her to continue. How do you balance the relationship between “you” as the subject of the work and “you” as the creator?

A.M.M.: I am the subject of much of my work, and I don’t shy away from it. But this character does not exist, and I seek to bring it into existence by infusing it with a selection of character traits, emotions, and life experiences inspired by my own observations of myself. There are indeed intense scenes, because that’s how I want them to be. I want maximum contrast between the most mundane detail and the most profound human manifestation. I succeed to varying degrees, it’s an intuitive process that I don’t intellectually fully master, but I never lose my focus. I am an observer and I record by replicating what I observe.

O.F.: What is your relationship with painting, with pictorial realism? How important is drawing for you as a starting point for exploring themes?

A.M.M.: Following on from the previous question, realistic drawing and painting produces replicas, and the most beautiful thing about it is that no matter how well you replicate something, there are always differences that create a comparison between the subject and its representation. And this draws attention to how much time you spend in these states and practices. This creates a system consisting of the subject, the drawer, the act of drawing and the drawn image, and the totality of the phenomena that occurs in this system is its artistic part.

O.F.: Drawing is just one step away from animation. And it seems to be an important one for you, although your work is often read in the light of painting. How did this transition happen? And what was important for you to notice, and to portray, other than the canvas or paper?

A.M.M.: It’s not an obvious transition, and it took me many years to do it. The first observation that led me to animation is that when you draw, from the very beginning, when you mark the paper with the first dot, the image begins its process of emergence with a certain degree of independence that you cannot control. That first dot already has a role in the final image, but even though you have drawn the dot yourself, you cannot yet determine what that role is. The image is always ahead of you, and that has fascinated me for years. I wanted to document exactly what I was drawing, in real time, so I could then look back and see what was happening. If you have the patience to look, the animation unfolds in front of you which, to me, is absolutely charming, but it can also be boring if you are not interested. And to overcome this boredom, I have found a few formulas, and after several experiments, and I have worked some of them out. While documenting the appearance of a particular image, I now want to introduce moments of delight and reward for the viewer, who is given the opportunity to recognise moving characters, abstract signs suggesting figuration, or glimpses of narrative.

There are animations hidden within any painting or drawing, or any work of art. And I am referring to a processual, not to the concrete meaning of the term ‘animation.’ I use this medium in a different way to other artists. Linguistically, the correct form would be ‘moving images.’ The way I see them is without sound, always accompanying a static image, and displayed as close to the image as possible.

My animations are evidence that something happened.

O.F.: Tell me about your intervention at the Institute of the Present and the main piece that will occupy the space: engaging activities, …Back to All NightCrawler. We find you in the studio, in the midst of (somewhat ambiguous) activities; we are invited to look around your studio space filled with other works, recalling the pictorial technique of mise en abyme so loved by certain Flemish or Spanish painters. There are many interpretations, of course, and we can imagine our own scenario, our own ways of working with these aspects of personal life. They can reshape generic answers about the condition of the contemporary artist, but at the same time they help us understand who Ana Maria Micu is and what her world is like.

A.M.M.: The idea behind this work came to me when I suddenly noticed that I could fit in this place where I usually keep a box, constrained. The space left after removing the box, where it fits perfectly, is too big for the shape of my body, and it may even look like a miniature home, an improvised shelter in the corner of a room. Or it may look like an entrance to some underground place of immense proportions, where I could fall or be thrown into. There is some intentional ambiguity, allowing for multiple interpretations. It is good to keep the work open. And I am opening it up even more with this drawing spreading into a mural made of black adhesive cut-outs, with a more graphic look, which is the premise for an animation in which a character inspired by a video of me stands up from a crouched position.

___

ANA MARIA MICU is a Romanian visual artist from Botoșani. She mostly paints, but sometimes switches to other mediums, such as drawing and animation. She uses as a source ideas and images that she observes in relation to changes in her living space, in which she also works, or negotiations on resources required by an ambition to garden in inappropriate conditions.

OTTO FELT is a German-born writer based in Rockport, Massachusetts. Felt studied and teaches comparative literature and art history, and aspires to devote himself entirely to writing and publishing his novels. He is a collector of artist books, with a particular interest in Eastern European and South American art.

___

In the frame of the THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE initiative, the Institute of the Present puts forward a series of interventions taking place in its own working studio in Bucharest, addressing the present and triggered by the way in which the independent artistic platforms and artists choose to respond to the energies of the context in which they operate. THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE is above all conceived as a place for dialogue, sharing of individual and collective experiences that are hosted in the septic terrain of the white cube, but in a working studio of 50 sqm. THIS IS NOT AN ARTSPACE is conceived by Alina Șerban and Ștefania Ferchedău in the frame of the artist and theory resource platform the Institute of the Present.

The series is organised in 2023 in the frame of the residency project “COLLEGIUM. A Possible History of the Invisible”. Cultural project co-funded by the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. Visual identity: Daniel & Andrew Studio (Andrei Turenici)

The project does not necessarily represent the standpoint of the Administration of the National Cultural Fund. AFCN cannot be held liable for the content of the project or the manner in which the outcomes of the project may be used. These shall devolve entirely on the beneficiary of the financing.

Contact: [email protected]

MEDIA REFERENCES

[text, EN] Maria Mănăilă, Ana Maria Micu – Left Hand to Distant View, Contemporary Art Friday, 14 April 2023

[audio, RO] Parkour sonor / Ana Maria Micu, The Institute of the Present Podcast, 27 martie 2023

engaging activities, ... Back to All NightCrawler, 2023, charcoal on toned canvas, 150 x 175 cm.

engaging activities, ... Back to All NightCrawler

animation from 25 wall drawings made with vynil cuttings | 14s loop | 3840 x 2160 px | no audio | 2023

AP from Edition: 3 + 1 AP